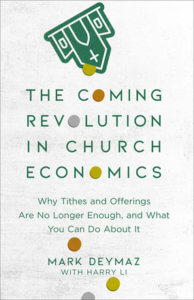

What if tithes and offerings no longer support your church’s operations? How can you create multiple streams of income by leveraging the value of your congregation’s people, programs, money, and buildings? This recap of a 2020 Leading Ideas Talks Podcast features a discussion between Mark DeYmaz and Ann Michel of the Lewis Center Staff on The Coming Revolution in Church Economics.

Listen to this interview or continue reading.

Ann Michel: You’ve written a book with Harry Li that is provocatively titled The Coming Revolution in Church Economics. Revolution is a strong word. Can you describe what you mean by that?

Mark DeYmaz: It reflects the need for pastors and churches to get away from relying simply on tithes and offerings for funding their work and to move toward a model where they create multiple streams of income. The church essentially is an economic system. Churches provide several goods and services to people: good worship, children’s programs, someone to preach the Word, baptize, bury someone when they pass, show up at the hospital, organize meals when you give birth. Think about church as a business model. A church provides goods and services to people, and traditionally the way that is paid for is through tithes and offerings.

But due to a variety of factors, some already in play and some looming in the future, we need a disruptive shift in our approach to funding the church. Middle-class wealth is the lowest it’s been since 1947 because of demographic shifts, increasing diversity, wealth gaps, and the financial burdens of the middle class. Moreover, people born after 1964 (Gen X, Millennials, and Gen Z) don’t think about money and giving in the same way that people born before 1964 think about it. And some local entities are rethinking the tax exempt status of local churches. Your county might decide to tax your church property as they do now in Pennsylvania.

So, simply put, there is a growing need for churches to create multiple streams of income. To say it another way, how can pastors and ministry leaders learn to leverage the assets of a church — people, money, and buildings — to bless the community and to advance the common good and the gospel? How can they bless the community but at the same time generate some measure of sustainable or profitable income? In the future, it won’t be just tithes and offerings, but it will be other methods of monetization of existing services, profitable business ventures, and enterprise — a combination of things — that will fund the church.

Ann Michel: For a number of years, we’ve observed that some churches, particularly in urban areas, are becoming more strategic in leveraging the value of their property through rentals, community partnerships, or property redevelopment. But some of the ideas in your book go well beyond this. For example, you write about monetizing certain services that churches typically provide, like selling coffee rather than giving it away, or having staff members raise money to support their own salaries or contract out their services. I find many of your suggestions really novel and some even controversial.

Mark DeYmaz: Well, that’s true. But it’s what we at Mosaic Church have had to do as a multiethnic, economically diverse church plant in the urban center of Little Rock. When it comes to the finances and economics of their churches, most pastors in America are, in my opinion, simply managing decline. They are not leading into the future. And like the frog in the kettle, they don’t even realize it because the only tool in our toolbox is try to get more people to come to our churches.

The traditional assumption is that the way we generate more funding for the church is to attract more people to the church. Fulfilling the Great Commission wasn’t just a matter of saving souls and extending the gospel, it was also our funding model. More people meant more money. But early on, we recognized that the more people who joined Mosaic Church, the more money it cost us. When you are attracting diverse people and the urban poor, the traditional model of tithes and offering is insufficient.

Here’s the problem. If a 65-year-old attending your church dies or moves to a different state and their giving goes away, how many millennials will it take to replace that giving? Nobody has done a study on this, but every time I talk about it, people say “Maybe 10.” Let’s just say it takes 10 millennials to replace that 65-year-old’s giving. Then, what is the customer acquisition cost? What do I have to spend as a church to attract a millennial versus what I have to spend to attract someone who is 65? When you say to that 65-year-old, “We teach the Bible. We’re exegetically sound. We love and care about people.” They say, “Hey, that’s good enough for me.” And they’ll show up. But the millennial will ask, “What else do you do? What about your social justice side? What about your compassionate work? How about your children’s programs?” And all those things cost. Now I’ve got to buy a laser light show and a smoke machine. I’ve got to wow everybody, and that costs the church money. Right now, we are like hamsters on a wheel. We’re chasing more people, but with that chase comes the expenditure of more money to attract them, and you’ll never catch up.

So, we propose disrupting that economic system. We need a multitiered strategy for funding the church. Yes, tithes and offerings. But we also have to learn how to attract local, state, and federal grants. And, on top of that, how do we actually create or generate profitable and sustainable income through business enterprises?

Ann Michel: The Lake Institute’s 2019 National Study of Congregations’ Economic Practices found that 81% of the revenue that comes into congregations is from contributions. Another 13% is from other traditional sources like fundraisers and endowments. And about 6% is coming from rentals. And some of the more innovative funding strategies you write about don’t even register on the scale. I share this not to dispute your point, but to suggest that the future you’re pointing to is pretty far beyond the current practice of most congregations. It’s going to require a different mindset and a different set of competencies. How can congregations, denominations, and even theological seminaries begin to help people think differently about church finances?

Mark DeYmaz: You’re absolutely right. I’m proposing a disruptive model at a time when the economic system of the church must be disrupted if it is going to be sustainable. The Church will always survive, of course. But how many churches will be around? And how many will be thriving in the future rather than merely surviving? We are talking about disruption, and change is never easy, which is why we describe this as a coming revolution.

If you are a pastor, this can sound very overwhelming. You might say, “Hey, I just signed up to preach the gospel, care for the sick, and to love, serve, and disciple. I don’t understand business.” But as pastor, you don’t have to be the person who delivers on all these fronts. However, you do need to build a team or actually a team of teams. Think about it like a three-legged stool. You need a spiritual team, a social team, and a financial team.

The spiritual team is your church and all the things that you do — evangelism, discipleship, baptizing, small groups, children’s ministry. That’s the game of the spiritual church. It’s led by a senior pastor, and it’s funded primarily by tithes and offerings.

Then the second leg is your social justice and compassionate work. You create a separate nonprofit that’s led by an executive director to solicit local, state, and federal grants, donations from other churches, human resources from other places. You move your justice and compassionate work out from under the budget of the church on the spiritual side into the social justice side because you can’t get local, state, and federal grants as a church for a program. But if you put it under a nonprofit, you qualify and you can get it. So, this is a smart funding strategy to advance social justice and compassionate work in the local community. You’ll get way more money than tithes and offerings could ever afford you to advance those goals.

Then the last leg is the financial leg. The head coach of that would be a CEO type who is going to help you rent that facility or develop property, help you monetize existing services, help you start brand new businesses, and generate an ROI (return on investment) or a profitable, sustainable income stream on the third leg.

And each team functions as a separate unit. And it’s overseen, of course, by the leadership structure of your church. The combination of those three teams playing effectively is not only going to move the church from mere survival to stability but ultimately to sustainability and effectiveness in the future.

Apply by February 15 for Leading the Church in a Post Pandemic Culture, a new Doctor of Ministry in Church Leadership focus from Wesley Theological Seminary and the Lewis Center for Church Leadership. With this track, clergy will receive the enhanced knowledge, skills, and motivation to increase congregational and denominational service, vitality, and growth in the post pandemic world. Learn more and apply now for May 2023 at churchleadership.com/dmin.

Apply by February 15 for Leading the Church in a Post Pandemic Culture, a new Doctor of Ministry in Church Leadership focus from Wesley Theological Seminary and the Lewis Center for Church Leadership. With this track, clergy will receive the enhanced knowledge, skills, and motivation to increase congregational and denominational service, vitality, and growth in the post pandemic world. Learn more and apply now for May 2023 at churchleadership.com/dmin.

Ann Michel: It seems there’s a missional advantage to this, as well. It isn’t just about economic survival, it’s about presenting your church to the community in a different way, about making your church more present to the community, whether it’s through partnerships or retail space or the way you are using your building.

Mark DeYmaz: Yeah. I really appreciate you bringing that up. This isn’t about us sitting back and getting rich, fat, and happy or about pursuing economics in a way that is mercenary. This is about advancing a credible gospel in an increasingly diverse, painfully polarized, and cynical society. It’s about being able to sustain our work long term. If we keep giving everything away for free, we’re not going to be here in ten years, so it is about the mission.

I believe in “just economics.” By “just economics” I mean “justice.” And just economics is the most effective evangelism strategy we have for the 21st century. In the 20th century it was explanation: How did people come to Christ? You bring Billy Graham to your city. He clearly communicates the gospel and people get saved.

In the 21st century, explanation doesn’t cut it. It’s demonstration. We have to demonstrate redemption. You have to demonstrate the hope of the gospel. In Matthew 5:16, Jesus didn’t say, “Let them hear your good words.” He said, “Let them see your good works.” Rather than buy land and build buildings, when you repurpose an abandoned Walmart or Kmart or Toys R Us, you don’t have to preach redemption. You just redeemed property. Everyone in the community sees it. It leads to job creation, a reduction in crime around the facility. It leads to new taxes being generated for your local community and many other social goods. And that’s what people pay attention to. That’s what is going to attract those who are disenfranchised and cynical about the church — when we are creating jobs, lowering crime, repurposing abandoned property, and generating tax revenue. That’s what gets the attention of the world and gives us the entrée to explain a credible gospel rooted in our good works that they see. And they ultimately come to recognize God in us, Christ in us, and it becomes a compelling witness.

And this is not merely a matter of economic survival or sustainability, or an evangelistic strategy. It’s also a matter of stewardship. The American church tends to think about its stewardship responsibilities in three ways. The first pertains to the care of our buildings. We own this building. God gave us this building. And we’ve got to take care of it. So, we mow the grass. You got a hole in the wall, you fix it. You’ve got a pothole in the parking lot, you fill it. The second pertains to accurately accounting for the money we receive. And third, we must clearly communicate to donors what we receive and where that money is going, how it’s being spent. Those three things essentially define good stewardship for the American church and the establishment.

Although I agree with the importance of all three of these practices, biblically speaking, exegetically speaking, that’s not what defines good stewardship. It’s the story of the stewards, right? And the master gives them five, two, and one. And one guy says, “You gave me five. Here’s your five and I made you five.” Another says, “Here’s your two and I made you two.” But one guy sat on his asset. That person who sat on his asset and buried it is called the wicked, lazy slave.

The American Church right now is literally sitting on billions, tens of billions, hundreds of billions, some say, of undeveloped assets buried in the ground. Lazy, wicked slave. For instance, a church of 65 people has a $2.5 million dollar endowment in the bank, but nobody is being saved, the community isn’t being impacted. But, by golly, those 65 people are proud of the fact that they have $2.5 million in the bank. Or it’s a church that owns 40 acres of land just sitting there undeveloped. I could go on and on about buildings all over this country that are used on Sunday mornings but at no other time during the week. That equates to the burying of assets. And that, by Christ’s own definition, is wicked and lazy. Good stewardship is taking what I have and doubling it; it’s leveraging it to generate even more and more possibilities. That is good stewardship.

What about the person who says, “What are you talking about? The church should just preach the gospel and trust God to provide.” Well, if someone says that to me, I say, “Let me ask you a question. Have you ever been to a doctor? Have you ever signed a loan to buy a house or car that you couldn’t otherwise afford? Have you ever taken medicine that a doctor prescribed?” I can say, “Where’s your faith? Why don’t you just sit around? Why do you get up every day and go to a job and collect the paycheck and work hard to get raises? Why don’t you just sit around your house and read the Bible and pray all day and then check your mailbox for money?” So, it’s about good stewardship and exercising intentional faith. There is a theological mandate to shift our thinking not only for economic reasons, not only for the justice witness, but to be faithful and good stewards.

Ann Michel: I’m glad you brought up the theological question. I agree very much with your interpretation of stewardship involving not just maintenance but the responsibility to use things fruitfully for God’s purposes. The ability to think differently about possibilities, assets, and resources is a way of breaking free from scarcity and claiming God’s abundance. But I worry that, if the church gets more concerned about making money in the marketplace and less concerned about cultivating generosity, we could avoid our calling to help people learn the importance of giving.

Mark DeYmaz: We say yes to tithes and offerings and yes to generosity for all the reasons you said. But also yes to what we are talking about — church economics. It’s not a displacement of what is, it’s adding an additional layer to how we are thinking. Could people take what we write and, in a sense, run with it and all of a sudden become a big business machine? Yes, they could do that. People could do that.

But here’s the thing. People are already doing that. There have always been people who have been leveraging the Bible, God, and the Church for their own human ends. We didn’t start that. That’s already happening. But the fact that it is happening or is a potential danger shouldn’t stop the rest of us who would build accountability, who aren’t doing this by ourselves, who are building teams around us in order to chase this dream of justice economics, not just for stability but for sustainability of our work for the long-term. You’re right. There is a danger. But by the way we construct the models, by the accountability we build into the system, we can keep the mission, just economics, at the forefront as a credible witness.

Ann Michel: I do think that the church is always at risk, whether it’s operating in the old paradigm of tithes and offerings or whether it’s operating in this new paradigm, of bringing only a transactional mindset to money. Regardless of the approach to financing or economic sustainability, we in the church need to see finances through more than just a transactional lens.

Related Resources

- The Coming Revolution in Church Economics by Mark DeYmaz with Harry Li, published by Baker Books, a division of Baker Publishing Group, 2019. The book is also available at Cokesbury and Amazon.

- Ways Your Building Can Generate Income and Bless Your Community by Mark DeYmaz

- Finding New Resources to Support Your Church’s Ministry, a Leading Ideas Talks podcast episode featuring Sidney Williams

- F. I.S.H. Differently! Take Stock of all Available Capital Resources by Sidney S. Williams

If you would like to share this article in your newsletter or other publication, please review our reprint guidelines.