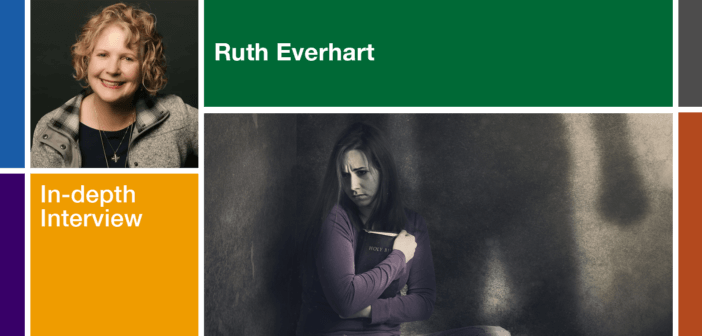

How can the church confront its complicity in sexual abuse and misconduct? In this interview, Ruth Everhart, a leading voice on issues of sexual abuse in the church, says congregations must create safe spaces for victims to share their stories while committing to appropriate measures to both prevent and respond to incidents of misconduct and abuse.

Listen to this interview, watch the interview video on YouTube, or continue reading.

Ann Michel: This subject is deeply personal for many people, as it is for you. I learned in reading your book that you were raped at gunpoint as a college student, that in your first pastorate, you were groomed and sexually abused by the church’s senior pastor, and then you suffered the indignity of having your complaints trivialized and rationalized away. It’s a harrowing, painful story. But you believe the church must listen to the stories of victims and survivors — stories a lot of us would prefer not to hear. Why is telling stories so important?

Ruth Everhart: Thank you for acknowledging how deeply personal the subject is to me and just everybody involved in the subject of sexual abuse in churches. I think the reason stories matter so much is that’s how we get at truth. So often, the person telling the story is the person who has power. So, to center the story on victims and survivors completely changes the narrative and changes how we look at the subject. I think that was the great revelation when the #Me Too movement burst on the scene. It framed a different kind of a narrative, and it allowed women’s voices, often men’s voices too, but the voices of victims and survivors to be heard. So, it’s absolutely essential to tell stories. And it’s not incidental that scripture is completely full of stories. It’s a big storybook. And that’s why I had the idea of intertwining the biblical stories with contemporary stories to see how they informed each other.

Ann Michel: In the opening of the book, you say “story is the way that we change our culture, the way that we define our culture, and we can’t really change things without being willing to tell stories.”

Ruth Everhart: I think that’s true of every justice issue. We don’t really have the eyes to see injustice until we see it interpreted through somebody’s story. Seeing the issue from a distance just isn’t powerful enough to affect the necessary cultural change.

Ann Michel: In 2018, as the #Me Too Movement was so in the news, Christian Century published an article you wrote, “Women of the Bible Say Me Too.” It lifts up the stories of Tamar and Bathsheba, Dinah, and other biblical women who were victims of sexual violence and abuse. And your book uses those biblical stories as a source of solidarity and spiritual insight, artfully interweaving them with your own story and the stories of other survivors. But at the same time, these stories remind us of how much misogyny and mistreatment of women is in scripture and how those stories have often served to normalize or legitimize the mistreatment of women. Not everyone brings the same enlightened feminist perspective to scripture that you do. And so, in our day-to-day ministries, how can we prevent the Bible from being used as a cudgel against women?

Ruth Everhart: Well, we can only control how we use the Bible. We can’t control how others use it. But we can demonstrate a different way to use scripture. Since the pandemic shutdowns, every preacher is a media preacher, right? We’re on livestream or YouTube and it is possible to disseminate our message more widely. So, it’s important to be really conscious of how we use the Bible and to be informed by other approaches — liberation theology, queer theology, feminist theology, womanist theology — and then be self-evident about your work with scripture. In a sermon or Bible study, really plunge into scripture, wrestle with the text, and do it as transparently as possible. Then, when we hear someone use the Bible as a cudgel, we call it out, just as we would if someone told a racist joke or made a misogynistic slur. You can say “No. That’s not really what the Bible is doing. I read the Bible differently than that.” But that requires being comfortable in the Scriptures. Sometimes we back away from that kind of engagement because we don’t want to weaponize the Scriptures. And it’s challenging because our country has become so polarized. But we can only do our part and call out what we see as best we can.

Ann Michel: The stories in your book really helped me see how terribly unprepared local congregations are if issues of sexual abuse or harassment arise, for all kinds of reasons. But one reason is that it’s often volunteer leaders — officers in the church, members who serve on a personnel committee — who are on the front line in dealing with allegations, complaints, or suspicions. How can we better prepare such leaders to respond to abuse and misconduct?

Ruth Everhart: That’s right. We’re really placing professional-level work in the hands of people who are essentially amateurs. They are well-meaning people, but they are not prepared to deal with something as explosive as sexual harassment and abuse. And I sympathize with the fact that they are not prepared for what they have to manage. We have to be more intentional about equipping them. You can’t wait until an accusation is made to train people on how to respond. You have to get ahead of the issue and set up training opportunities when the world isn’t burning. You need to talk about how this should be approached, to learn the basics of trauma-informed care, to master the vocabulary, to talk about centering the victim and not the perpetrator, to talk about the role of the legal or the justice system.

There are so many ways that you can talk about this in adult education and in leadership training. I’m a Presbyterian, and in my presbytery, the National Capital Presbytery, we’ve been required to do boundary training for a couple of decades and to renew it every three years. There are online learning opportunities out there. You have to come at it from different ways so that people are more equipped.

Ann Michel: You explain that there are two issues within the purview of local congregations — the issue of preventing sexual misconduct and then the issue of responding to it. Some of stories in your book happened some time ago. With the heightened level of concern and publicity in recent years, do you feel that things are getting better?

Ruth Everhart: In terms of prevention, it’s become common for churches to have some kind of a safer church policy that protects children and youth. And that’s wonderful. We need to be at that place where we know safeguards. In terms of responding to abuse, sometimes allegations like mine are from the past. That’s difficult because you are bringing a more contemporary lens to something that may have happened a long time ago. This happens with sexual abuse stories all the time. People bring up allegations of things that happened a while ago. And churches are becoming a little more adapt at listening to that. Some of them are actually lifting the statute of limitations, just like some of our legal systems are, and that’s really important.

I do see a few churches that have moved much more quickly to using the legal system. There has been a tendency in the church to view any kind of sexual misbehavior as a “sin” rather than a “crime.” We need to see it as both. We need to say, “This is a crime that needs to be prosecuted in a court of law.” If you put it in the category of sin — and we see this happening in some of the Southern Baptist Churches — perpetrators can make a public confession, and receive a standing ovation for having done so, without the next steps of accountability, punishment, and restitution. So, I would love to say that things are getting better. And I think they are getting better, incrementally. But it’s a big topic for the whole church, not just for the mainline Protestant churches that I focus on.

Ann Michel: So often, churches wrap these problems in a cloak of secrecy and confidentiality that allows them to remain hidden or ignored. In your book you wrote that “confidentiality can become complicity.” How can we balance appropriate levels of confidentiality with the need for truth telling and accountability?

Ruth Everhart: It’s understandable when people get on the wrong side of this, not because they’re evil people or because they’re trying to cover something up. Usually, it’s the people who value clergy and value their role within the congregation that might be most likely to protect them even when they have been abusive. What’s the difference between confidentiality and secrecy? When is privacy appropriate and when does it become twisted? When is privacy weaponized? We need to ask, who is it that’s suffering? And who are we protecting? If our concerns about not telling a story are to protect the person who is at fault, that should make us pause, right?

But it’s not so easy because our culture has a long history of trying to protect victims. I was raped at gunpoint in my senior year of college. I was only 20 years old. It was a long time ago, but one of the dynamics at that time was to protect our names and not reveal who we were. Did that mean we had done something wrong that we needed to be protected from? It’s not an easy subject. You get into who’s at fault, who benefits from being hidden.

I do feel our cultural norms are shifting a little bit. I see victims stepping up and claiming their story a lot more quickly and a lot more forthrightly than they used to. And I applaud that because it reinforces that the victim is not to blame. I always say, “Why is it so different than breaking your leg?” It’s this really unhappy thing that happened to you, but it doesn’t mean you were at fault. And to treat it as if it is just unspeakable, to say we cannot talk about this — I just disagree with that wholeheartedly. We have a whole treasure trove of scripture in which these things are not unspeakable. There are lots of stories about sexual assault in the Bible. And we have a Savior who spoke about things that other people didn’t want him to speak about. This is why we need books and podcasts and institutions and sermons to break that open and let the light shine into it.

Ann Michel: In the church I attend, about five years ago we had a clergy person who had to leave the ministry because of misconduct. From the point of view of a parishioner, we were left very clueless about what was happening and why. I think our denominational leaders were much more concerned about legal liability than transparency and truth telling. And as a result, a lot of people are still confused and conflicted about what happened.

Ruth Everhart: Oh, it makes me crazy! That’s a common story. And the thing is, they can talk about fiduciary responsibility or being a steward of the institution, they can say they’re doing their job, but don’t we live by a different set of rules? One of the stories in my book was about a youth pastor involved in sexual misconduct. And the senior pastor told the story in worship. He did so against the advice of the congregation’s insurers. So, it takes a real boldness to step outside that norm.

Ann Michel: The conversation about sexual misconduct in churches tends to focus on clergy as potential perpetrators of abuse. But the problem isn’t limited just to clergy or to what happens in the church. I recently heard you say that “when we look out on our pews on Sunday mornings, there are people in worship who are both abusers and victims of abuse.” How can the church minister to this reality?

Ruth Everhart: Yeah. That’s a tough one. I think pastors have to develop almost a “spidy sense” about who out there might be an abuser. I try to sniff them out. And then I do one-on-one conversations with people who I think might be at risk. But there’s another issue that’s even harder to talk about. I don’t think men have a place to talk about growing up in our culture of misogyny and toxic masculinity. What messages did they receive about interacting with women? How many men may have done something at some point in their lives that they are now ashamed of? Perhaps they were unaware of the dynamics at the time, but now they feel deeply chagrined. Do they have a story about a time when they may have abused their power?

We talk about abusers like they’re all at one end of the spectrum and they’re all predators. There are predators out there. And our churches can be breeding grounds for them. But what I’m talking about is the other end of the spectrum, your decent guy who grew up thinking at a really gut level that he’s more valuable than any of the women he comes in contact with, which gets translated then in all kinds of ways that become abusive. Can the words of Jesus shift this guy’s paradigm? My wildest dream is to have a group at a church where men sit around and actually talk about this — not how they’ve been victimized but how they’ve been victimizers — and to shed the light of Jesus on that. I think that may be the next frontier in this movement.

Ann Michel: You say that sexual abuse can’t be addressed without addressing patriarchy. Another root cause in the church is clericalism. And it seems to me that putting so much energy into trainings on preventing and responding to abuse is putting a technical bandage on the adaptive challenges of making the church more equitable and valuing women and victims. And that’s a different kind of work than just sending people to Safe Sanctuaries training.

Ruth Everhart. I think the culture shift is always the hardest work.

Ann Michel: In the final chapter of your book, you focus on action steps for congregations. Some are low hanging fruit, and some involve much deeper work around lament, listening, and creating safe spaces where people can have these conversations. Can you share some of the things a local congregation might do?

Ruth Everhart: The low hanging fruit involves signaling to people that the church is a place where you can talk about difficult things. Maybe it’s putting a hotline number in a restroom. Maybe it’s having a sermon series with “#Me Too” in the title and putting it on your outdoor sign as a signal that says, “Look, they are talking about that there.” You can talk about it during April, which is sexual assault month, and during October, which is domestic violence month, capitalizing on those cultural moments. You can have an article in your newsletter, “What does grooming look like?” Something that goes a little deeper and communicates the church is a place where it’s safe to talk about such things.

I think the next layer, then, is to create forums such as adult education classes. And then there is preaching. That was my big thing. The Christian Century article you referred to earlier was focused on really encouraging people to preach on some of these stories in the Bible that we ignore. I have preached all those sermons in a church that decided they didn’t really want me there anymore. There’s a cost to doing this work. I’ve paid the costs in many different ways. I understand why people want to tread cautiously. Some people can only tolerate this tiny amount of awareness, and they get very nervous. People don’t like to talk about sex in church, and unfortunately sexual abuse gets put in the “sex” bucket instead of the “violence” bucket, right?

Ann Michel: I think that’s why the conversation so often gets shut down in the church. People avert their eyes. It’s embarrassing and shameful for them. You wrote that “people need a stout heart and a strong stomach” for this work.

Ruth Everhart: Yes. You have to constantly frame this as a justice issue. If you frame it as just a women’s issue it gets sidelined. To me the most important thing is feeling that I’m not doing this alone, to feel that there are partners out there. I do it because I know there are partners out there listening and I value them. I value each story. When I sign my book, I sign it “Every story matters.” Because it does. Every effort to bring justice to a story and to bring the light of Jesus Christ into a place that is dark and painful is important. We have to get out of our comfort zone to do that. But that’s what Jesus asks us to do.

Related Resources

Related Resources

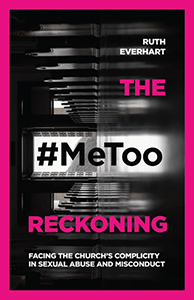

- The #MeToo Reckoning: Facing the Church’s Complicity in Sexual Abuse and Misconduct (IVP, 2020) by Ruth Everhart. Also available at Cokesbury and Amazon.

- The #MeToo Reckoning Workshop, a self-paced, online workshop by Rev. Ruth Everhart and Dr. Eileen Campbell-Reed. Learn more at rutheverhart.com and enroll at eileencampbellreed.org.

- Keeping Our Sacred Trust, online courses on sexual ethics and ethical boundaries in ministry offered by the Lewis Center for Church Leadership

- 3 Actions Churches Should Take in Light of #MeToo by Phill Martin

- 7 Ways Congregations Can Respond to the #MeToo Movement by General Commission On The Status And Role Of Women