Do you long for church to be a place where people can discuss real life challenges openly and honestly? Ann Michel of the Lewis Center staff interviews pastor and author Elizabeth Hagan on what it takes to be a “brave church” willing to tackle tough but important subjects.

Ann Michel: In many congregations there’s a “cone of silence” around certain subjects seen as difficult or impolite or off limits. What do you see as the contours of this reticence and why is it concerning to you?

Elizabeth Hagan: My experience with this topic began many years ago when I was personally struggling with infertility. I was going through a very difficult, painful experience while still trying to be there for my congregation and do my job to the best of my ability. I found it very hard to talk about my own experience of deep pain and loss and grief. And out of that came my first book, Birth: Finding Grace through Infertility. But as I talked about that book in churches and at conferences, I was deeply shocked by how hard it was to even voice the word “infertility” in many ministry settings.

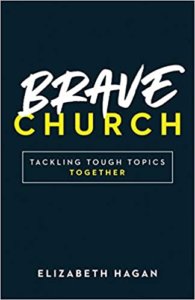

Even colleagues of mine, some of whom had dealt with infertility or other really hard things themselves, didn’t want me to talk about it in their churches. They wanted me to tone it down a little, to talk about grief in a general sense, but not get into the specifics of topics like infertility. I began to think, “This is not the way it should be.” I believe church is a place where all people should be welcome with all their pain and all of their stories and all of their experiences of God. And I began to dream about giving tools to churches to help them begin to talk about such things with bravery. And that’s how Brave Church was born.

I believe church is a place where all people should be welcome with all their pain and all of their stories and all of their experiences of God. And I began to dream about giving tools to churches to help them begin to talk about such things with bravery.

Ann Michel: I’m sure that resonates with a lot of people. We all know certain subjects are considered impolite in church. But I want to juxtapose that reticence within congregations with a broader culture in which it sometimes seems that virtually nothing is off limits. People talk about some pretty private, salacious stuff in the grocery store tabloids or on social media or TV talk shows. So, I’m wondering, is the church just more buttoned up and old fashioned? Or do you think something else is going on?

Elizabeth Hagan: You raise some really interesting points. I think the church is designed as a “safe space” where people gather with like-minded folks who believe the same things about God and Jesus and the Bible and how to live out their faith. And within this safe place, we assume a common language of who we are and what we believe and what we think is important in life.

But for many, churches aren’t safe, even with the common denominators of theology or life experiences. Churches aren’t necessarily safe places for people who feel they can’t bring their whole self to church. Eventually those people seek community outside of congregational life, and that grieves me because I believe the church should be the family of God on earth.

It’s a beautiful experience to be around people who know and love you well. But we can’t find that sense of community if we’re not able to talk about what we’re dealing with, whether it’s an experience of racism, an experience of not being safe in our home with a partner who is mistreating us, whether it’s because we can’t have a child, or whether we’re struggling with mental illness. We all deal with many challenges in our lives. My hope is that churches step beyond just being “safe” and move toward being a “brave space” where even more people feel welcome to share their stories and be a part of the group.

I was taught a lot of theology as a child. You go to church. You learn Bible stories. You learn memory verses. I was a good church kid growing up. But I was never taught how to talk about things that happened to our neighbors or in our homes — like someone who yelled too much at dinner and how that made me feel. There’s a sense we have to bring our best selves to church. How dare we appear not fully put together? Because what will people think? And that’s hard.

Ann Michel: And this keeps lots of people away from church. Maybe it’s a single mother. Maybe it’s someone who’s experienced divorce. Maybe it’s an unwed mother. They get the impression that church people are so proper and good that they couldn’t possibly fit in. When people can only show their best side at church, it creates an unwelcoming environment for anybody who’s truly struggling with problems.

Elizabeth Hagan: I totally agree. It starts with the leadership. Nadia Bolz-Weber says, “We lead from our scars, not our wounds.” It’s not appropriate for pastor to be bleeding over their congregation when they’re in a really difficult place. But with time and perhaps help from outside professionals, we get to a place where we can talk about things that have been hard in our lives. I just long for congregational leaders to be able to just talk about their lives. Shame shouldn’t be the story we project to our congregants.

It’s a beautiful experience to be around people who know and love you well. But we can’t find that sense of community if we’re not able to talk about what we’re dealing with, whether it’s an experience of racism, an experience of not being safe in our home with a partner who is mistreating us.

Ann Michel: Many congregations today are having tough conversations around racism and political division. You address race and politics in the book. But for the most part, you address more personal subjects — infertility and marriage, mental illness, domestic violence, sexuality. You bring a very pastoral perspective. Do you think the same dynamics and rules are at play when discussing public issues as opposed to private issues within the church?

Elizabeth Hagan: Absolutely. Whether the subject is very personal like infertility or miscarriage or something that is a very public story like police brutality and persecution, these are things we must talk about in church. I piloted this project at my own congregation, the Palisades Community Church in D.C., a couple of summers ago. We found that just beginning these conversations, being open and hearing one another did some really powerful, new things that would have been uncomfortable in the past.

Ann Michel: I would imagine it really strengthens relationships and trust as well when you go to these vulnerable places within a group.

Elizabeth Hagan: It does. I’ve always thought a thriving congregation is a place where people know and love each other well. But if you do not know each other, you cannot love each other well. You know, pastors still need to be pastored. And with every person who’s pastored me, I’ve had the vulnerable experience of them truly knowing something that’s going on in my life. And in the churches I pastor, I see people really showing up for one another in such meaningful ways when stories are birthed.

Elizabeth Hagan: It does. I’ve always thought a thriving congregation is a place where people know and love each other well. But if you do not know each other, you cannot love each other well. You know, pastors still need to be pastored. And with every person who’s pastored me, I’ve had the vulnerable experience of them truly knowing something that’s going on in my life. And in the churches I pastor, I see people really showing up for one another in such meaningful ways when stories are birthed.

When we were talking about domestic violence, I discovered there were lots of women within my congregation who had dealt with this privately. They had never uttered a word. As a result, we decided to celebrate Domestic Violence Awareness Month. And it really helped bring to the surface this often unspoken topic. We put up signs in the bathrooms. And parents from the preschool started talking to me about domestic violence. That never would have happened without the brave conversation.

There’s a sense we have to bring our best selves to church. How dare we appear not fully put together? Because what will people think? And that’s hard.

Ann Michel: That’s a great example of how conversation leads to action.

Elizabeth Hagan: It does. But it has to start with saying the words. Someone in your group says, “This has been my experience of racism.” And you think, “Well, how is that? You seem like you fit in and everything’s fine.” But hearing someone say, “This is what it feels like to be me,” can have a huge impact.

Ann Michel: In some of these conversations, pastors and other church leaders may find themselves in places that are personally uncomfortable. A phrase in your book that struck me was “commit to discomfort.” Would you be willing to share how you’ve managed your own discomfort with certain topics?

Elizabeth Hagan: If you’re really tackling tough topics, it means there’s going to be discomfort. You might be called out on your own bias along the way. You may discover that what you thought was the perfect answer in a particular situation wasn’t the right answer. You might think you’re doing everything right; you might think you’re sensitive to the situations and perspectives or others. But then you find you’ve completely missed the mark. It can be something big, or it could be something little.

When I was the pastor of Washington Plaza Baptist Church in Reston, Virginia, we had a sister church relationship with Martin Luther King Christian Church, also in Reston. I was in charge of preparing the bulletin for a joint service. My normal practice is to not include titles in the bulletin. I’m just Elizabeth Hagan. And for church members in the service, I just put their names. And the pastor of Martin Luther King Church called me and said, “This is all wrong.” And she said, “Our church goes by titles. Brother. Trustee. Deacon. I need to be Reverend Doctor because we’ve lived in a culture that’s tried to take away our identity and our sense of self. The church is the one place where we feel like we can be whole, and we can be respected. And so could you please change all the titles?” You know, I could have been really offended in that moment. But I just said “Oh, of course! I’m sorry.” I wasn’t trying to disrespect anyone. But I was seeing it through my lens. I think staying in the discomfort means that we’re going to make mistakes. And that’s the beautiful part of learning and then being in community.

If you’re really tackling tough topics, it means there’s going to be discomfort. You might be called out on your own bias along the way. You might think you’re sensitive to the situations and perspectives or others. But then you find you’ve completely missed the mark.

Ann Michel: Your book outlines a really helpful set of rules for having “brave conversations” that call into question some of our normal ground rules for discussing controversial subjects. For example, many people will say, “Let’s just agree to disagree.” So, what’s wrong with that approach?

Elizabeth Hagan: To just say to someone you want to “agree to disagree” is to say, “I like you so much that I just I don’t want to argue with you.” Or it’s another way to say, “Could we please just be quiet?” The problem with agreeing to disagree is it silences people. It says their belief or their idea or their experience is not worth listening to. If we don’t agree to disagree, but we listen to one another with respect, we give everyone a chance to be heard. We are staying in that discomfort, which I think is really important to brave conversations.

Ann Michel: So sometimes if we disagree with someone, we might preface our remarks by saying “Don’t take this personally ….” What’s wrong with that approach?

Elizabeth Hagan: That’s another dismissive approach because it ignores the fact that I may have feelings and you might hurt my feelings. In brave spaces we own the impact of our words. We know we might hurt someone, even if we don’t intend to.

Elizabeth Hagan: That’s another dismissive approach because it ignores the fact that I may have feelings and you might hurt my feelings. In brave spaces we own the impact of our words. We know we might hurt someone, even if we don’t intend to.

Ann Michel: That’s really helpful. I didn’t realize how those common phrases could shut down conversation or invalidate what others bring to the conversations. Your book is a resource for church groups discussing controversial topics. You provide some specific ground rules that can serve as a covenant. But it seems to me this presupposes a certain level of trust and a willingness to engage. Sadly, that may not exist in all congregations. So, are there circumstances when it’s inadvisable or unproductive or maybe just not the right time to launch this kind of study?

Elizabeth Hagan: One person who read the book said to me, “I love this book and I love this concept. But my church doesn’t even feel safe, so I can’t even imagine how it could be brave.” That’s really important to recognize. But this particular woman is connected with a women’s group. Maybe that’s a better place for some of these conversations than her Sunday school class. You have to be aware of your circumstances. It may not be the right fit for you and your church at this time. At the same time, I feel so excited that this is the time for this book, and this is the time for these conversations. Because aren’t we so tired of the division in America right now, of the separation of the church? That we don’t feel relevant to things that everybody’s talking about? Things that are so important to all of us? I know that Brave Church asks a lot of pastors and congregations. It takes bold leadership to say, “I want to be a brave congregation.” I know it’s a big deal and I know it’s a big ask. But I think this moment requires us to step up to this challenge and to be brave because the world needs us to be brave. It needs us to talk about racism. It needs us to talk about mental illness. It needs us to help people feel less alone and less ashamed of what they’re dealing with in their life. And to me, it’s good news.

This moment requires us to step up to this challenge a because the world needs us to be brave. It needs us to talk about racism. It needs us to talk about mental illness. It needs us to help people feel less alone and less ashamed of what they’re dealing with in their life.

Ann Michel: Are there some smaller steps to begin to lay the groundwork in a church that isn’t totally ready to go to this brave place?

Elizabeth Hagan: I wrote this book with two audiences in mind. The first is church leaders who want a tool to help people feel more authentic in church. But I also wrote this book for individuals. I hope people struggling with some of these difficult experiences can find a sense of home and refuge in the book. I hope as they read it, they will hear their own story, they will know someone is nodding their head alongside them, and they will feel less alone. Someone who recently read the book said, “I feel this book will be a tool of reconciliation between me and my church. I’m really excited to take this book and give it to my pastor and say, ‘this has been my experience of racism and I want you to please read this and just take this in for a minute.’” And that kind of gave me chills. Because I thought, “Wow. It can be a gift for a person to feel more understood, to feel more heard.” And they can speak to their church leadership and say, “Will you please just digest this with me? Can we have a conversation after you read this book?” That felt really powerful.

Ann Michel: Can you share your vision of what would be different or better in our churches if we were places of more honest and candid conversations on tough topics?

Elizabeth Hagan: I believe that it would be a place where more people feel at home and more people feel welcome. We all want our churches to be welcoming. But many people can’t find a true spiritual home in a church that says, “These topics are off limits. We can’t talk about this here.” And aren’t we all looking for someplace where we feel we can bring our whole selves, no matter if it’s a church or somewhere else? We all need space to process and to grieve or to find resources. The church could be such a place. That’s the kind of church I want to go to — a church where I can pray not just for my Aunt Milda who has cancer but also for my neighbor whose daughter is in treatment for anorexia or where I could say, “I don’t feel safe here because we need to address some real institutional strongholds of racism. Could we begin that conversation?” Those places are really beautiful to me. And I think that the world is longing for these spaces, too.

Ann Michel: Elizabeth, thank you for sharing that vision.

Related Resources

Related Resources

- 5 Rules for Engaging Taboo Subjects in Church by Elizabeth Hagan

- Brave Church: Tackling Tough Topics Together by Elizabeth Hagan, available at Cokesbury and Amazon

- 5 Ground Rules for Candid Conversations by Tom Berlin