Craig Hill, dean of Perkins School of Theology, says that ambition and the desire for status are wholly natural, yet like other natural desires they are inherently ambiguous and must be kept in check. He says the most common strategy employed by the New Testament authors in response to conflicts over status was an appeal to the example of Jesus.

Status is not a gift of the Spirit. Ambition is absent from New Testament lists of spiritual fruit. Authority, honor, and rank are at best ambiguous scriptural categories. Still, Christians remain ambitious, desire status, and seek higher stations. Are they wrong?

In over two decades spent training Christian leaders, I have found no constellation of issues so seldom discussed and yet of such intense interest. Clergy may more comfortably converse about their sexuality or mental health than about their own need for recognition and affirmation — which, if they are honest, was part of their motivation for entering the ministry. Invite this conversation, however, and a lively, even liberating, exchange ensues. It is a relief not to have to pretend that we are unconcerned with our standing. Better to expose our veiled aspirations and attempt to think openly and faithfully about them. As Justice Louis D. Brandeis put it, “Sunlight is…the best of disinfectants.”

Jesus did not tell the disciples that their native desire for significance was wrong. Instead, he told them that it was misdirected.

A desire for status is wholly natural. We are by far the most social of animals, and social animals characteristically organize themselves according to status. The benefits are considerable, including diversification of roles, protection against predators, increased food gathering capacity, assistance with rearing offspring, and social support. But there are costs as well as benefits. Some risks, such as starvation and disease, are amplified in a community setting. Most animal societies exhibit a dominance hierarchy, which means that its advantages are not distributed equally. The alternative, however, can be near-constant disorder, competition, and strife, making the entire herd, pack, flock, troop, or pride less productive and more vulnerable.

Natural desires, while necessary, are also inherently ambiguous. This is as true of our longing for status as it is for our longing for the pleasures of sex and eating. These impulses are like a road with a ditch on either side. The ditch to the right is indulgence, which leads us to hurt ourselves and, especially, others. The ditch to the left is repression. We push the desire down, but all too readily it pops up elsewhere, often in disguise and often in even more dangerous form.

Fortunately, New Testament authors have much to teach us about this issue. The Greco-Roman world was thoroughly hierarchical and extraordinarily status conscious. Many early Christian communities were comprised of a highly unusual mix of people: highborn and lowborn, Jew and Gentile, literate and illiterate, masters and slaves. Entirely against the cultural grain, members of these groups were told, among other things, to call each other “brother” or “sister,” and to “outdo one another in showing honor” (Rom. 12:10).

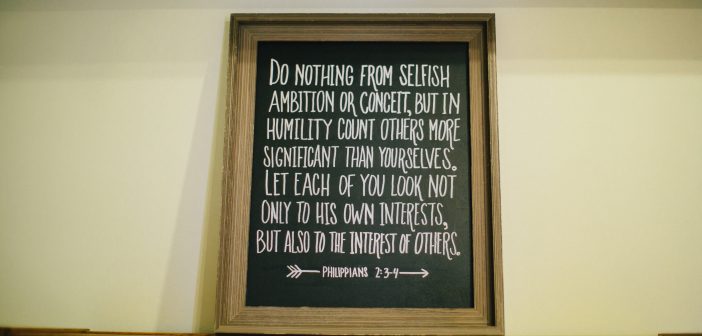

By far the most common strategy employed by the New Testament authors was an appeal to the example of Jesus. We all know the famous “Christ hymn” of Philippians 2:6-11. Often missed is what comes just before it: “Do nothing from selfish ambition or conceit, but in humility regard others as better than yourselves.” (Phil. 2:3) It is only then that Paul says, “Let the same mind be in you that was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God…emptied himself, taking the form of a slave” (vv. 5-6a).

We see the same pattern throughout the New Testament: Christological affirmations are offered in response to conflicts over status. That is precisely how many of the servant passages function in Mark, such as we find in 10:43-45: “It is not so among you; but whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all. For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life a ransom for many.”

Perhaps the richest resource for dealing with these matters is Paul’s correspondence with the church of Corinth. For many there, Christianity was simply a new means to a very old end, namely, social advancement. Among other things, the Corinthians boasted of their affiliation with a superior apostle (1 Cor. 3:4) and viewed spiritual gifts as status markers. Paul counters their pretentions by saying that they are not, as they thought, spiritual people, but rather “people of the flesh.” “For as long as there is jealousy and quarreling among you, are you not of the flesh, and behaving according to human inclinations?” (1 Cor. 3:3).

Many other New Testament texts equip us to overcome the all-too-natural inclination toward status chasing. At the center is Scripture’s teaching about justification. All of us need to be justified, but we are incapable of justifying ourselves, try as we might. No bank account is large enough, no job title impressive enough, to give ultimate meaning to our lives. It takes faith to believe in a wholly different system of value, but it is such justifying faith that holds the power to set us free to serve fully and joyfully in this world.

This is especially true for clergy, whom we expect to be highly motivated (or, we might say, ambitious), but also genuinely humble. Moreover, a life of service is inherently unfair. It requires strength — strength of character, strength of identity, and, above all, strength of faith. On the other hand, egocentrism, like that displayed by Jesus’ disciples, is a very human manifestation of personal weakness: “they were arguing with one another about who was the greatest” (Mark 9:34).

Jesus did not tell the disciples that their native desire for significance was wrong. Instead, he told them that it was misdirected. I suspect that is a word for us all.

Craig Hill’s most recent book Servant of All: Status, Ambition, and the Way of Jesus (Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2016) is available at Cokesbury and Amazon.

Jesus (Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2016) is available at Cokesbury and Amazon.

Related Resources

- Eerdmans Author Interview: Craig Hill, Servant of All: Status, Ambition, and the Way of Jesus

- “Who is the Greatest” — The Perennially Wrong Leadership Question by Lovett H. Weems, Jr.

- Servant Leadership: Jesus & Paul by Ann A. Michel