Scott Cormode writes that pastors need to provide the theological categories to make spiritual sense of money and the issues that it creates.

There are many motivations that preachers use when they attempt to motivate people to give. Some talk about the good things that the money will buy — whether food for the hungry or electricity to light the sanctuary. Others talk about God’s commandments and make giving a matter of obedience. This is the biblical equivalent of the parent who says, “Because I said so.” And, then, there are preachers who emphasize the urgency of some crisis. “If you don’t give, we will have to close the project.” I disagree with each of these rationales.

Talk of utility (i.e., give to accomplish something) turns givers into consumers who purchase services. The problem here is that, in a world where the customer is always right, people begin to think of themselves as having control over which things get done. Almost every pastor has met parishioners who threaten to take their money elsewhere if they don’t get their way. A congregation’s primary responsibility is to serve God and not to be swayed from doing good by the giver who wants to have his or her way.

Likewise, the call to obedience is not the best way to inspire giving because it is too easy for the preacher to become the voice of God. Don’t get me wrong. I do believe that Christians should give because God commands it. But I also believe that the pastor who preaches such obedience as the primary motivation for giving runs the risk of claiming God’s authority for himself or herself. And, finally, the crisis appeal plays off what I believe is a distortion of God’s provision. It emphasizes what Walter Brueggemann has called “the myth of scarcity” rather than celebrating the God of abundance. In other words, if we continually emphasize scarcity, we run the risk of leading our people to believe that they (and not God) are the ones who provide.

I am not saying that it is always inappropriate to use these three rationales for giving. I have used each one and will no doubt use each again. Instead I am saying that they need to be used sparingly and thus cannot serve as the primary reason that we use when we call on people to give. What then is the best reason for people to give? I would offer three motivations in their place.

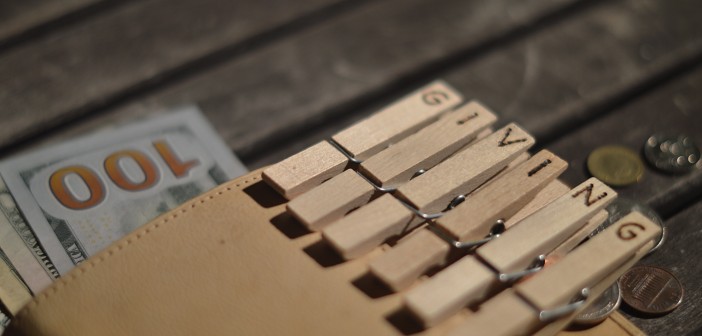

Generosity

First, we should each give because generosity is a good thing. It is the opposite of selfishness. It does not take a deep theological analysis to convince a congregation that selfishness is at the root of all kinds of evil. All they have to do is look around them — or to take a look at their own lives. Selfishness is one of the first negative behaviors we see in toddlers. It is one of the most difficult attitudes to root out in teens. And it remains prevalent in the adults most of us encounter each day. Selfishness in its various forms is rampant. Generosity is the antidote to selfishness. We sometimes think that the opposite of some sinful behavior is the absence of that behavior. But I would argue that the opposite of selfishness is not the absence of selfishness. The opposite is to do well — to practice generosity.

Responsibility

The second reason to give is that we each bear a responsibility for one another. I believe that we often create a free agent model of Christianity, especially when we talk about giving. The logic of our preaching often says that each individual makes his or her own decision apart from the community of faith. We certainly don’t talk about how much we give. In fact, that would be considered rude in most congregations. Yet, if we are indeed a community of faith, then we each bear a responsibility for one another. I am specifically not interested in having someone stand up in church and tell other people that they have to start giving their fair share. If, on the other hand, a pastor can help people see that they bear a responsibility to their neighbor, then that provides one more rationale for giving.

Sacrifice

Finally, there is a time and a place for talking about sacrifice. I hesitate to bring this up because the notion of “sacrificial giving” has been abused by generations of pastors. When I talk about sacrifice with a congregation, however, I start small. I want them to think about some small way that they can give up something. For example, my wife and I were talking with our children about how much we should give to various causes. At the end of the discussion we came to the question of how much we should donate to help two young persons in our church go to work for a summer in a Kenyan AIDS orphanage. We agreed on an amount. But my daughter did not think it was enough. So we asked her what she would be willing to give up in order for us to give more. She did not understand at first. So we explained the concept of sacrifice. In the end, she agreed to give up our monthly visit to her favorite restaurant so that we could increase what we gave to these women. It was not a big sacrifice in that it only netted a few more dollars. But it was, for my daughter, the next faithful step. And that was far more important than the money. It made her more generous, and it fought against the corrosive effects of selfishness. Sacrifice is an important category for people to have when they think about money.

People expect preachers to preach self-interested sermons about money — sermons designed to get the preachers more money. So we must defeat that stereotype by listening well to the anxieties that money brings out for people. But it goes further than that. We need to provide them with the language — the theological categories — to describe how to make spiritual sense of money and of the issues that it creates in their lives.

This article is an excerpt from Scott’s forthcoming book from Abingdon Press, Making Spiritual Sense: Christian Leaders as Theological Interpreters.