How can congregations support persons with dementia and their caregivers? Jessica Anschutz interviews Elizabeth Shulman, who offers an organic, three-part program to aid congregations in creating ministries to meet the needs of persons with dementia and their caregivers.

Listen to this interview, watch the interview video on YouTube, or continue reading.

Jessica Anschutz: I invite you to start off by sharing what inspired you to develop a guide for congregations and individuals to develop dementia caregiver ministries.

Elizabeth Shulman: I was serving as a pastoral care director for a 600-bed nursing home facility in Knoxville, Tennessee, and I did a lot of work in the memory care unit. It was Tennessee, the Bible belt, and everyone went to church. I primarily met with spouses but also children coming in to see their parents. They talked about how their church was the backbone of their growing up. Now that they were caring for a loved one with dementia, they were turning to their church for help, and the churches did not know how to help.

Now, 14 years ago, I was providing care in a different capacity to my husband. I realized that our sense of spirituality really impacts us and can give us an overview of all of our experiences. I decided to go back to school and get my doctorate in counseling. My focus was the experience of marriage for spouses because of my experience and that of spouses of Alzheimer’s patients. I interviewed spousal caregivers and I also interviewed pastors. I found that churches want to help; they just don’t know how. I wrote the book so that caregivers could share and pastors and other church leaders or congregation members could know how to better and specifically help.

Jessica Anschutz: I found the book to be a wonderful response to those needs. Tell us about the “Finding Sanctuary” program and how organic it is to a congregation or a particular community.

Elizabeth Shulman: I tried to write it so that it wasn’t just a set way to do something, but rather a way to speak differently to different congregations. There are essentially three parts. There’s a part for spouses to process their experiences and create a safe space for them to share with others what they are going through. Then a part for children to do the same because children and spouses can have very different experiences with caregiving. Their needs are different, so they each have their own group. Then, concurrently, there’s a group for pastors or congregation members who feel called to help serve this population but don’t know how. It walks them through what it’s like for a dementia caregiver both as a spouse and as a child. Their part of the program identifies gifts that they have. During the final week, all groups — the spouses, children, and congregation members — meet together. The caregivers have a list of needs that they have identified and the congregation has a list of gifts that they have to share. They compare to see where they can merge to form a ministry that’s unique to their congregation.

Jessica Anschutz: What a wonderfully organic approach. While I knew that more and more people were being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, I didn’t realize that there is now a diagnosis every 65 seconds. It seems to me that this is a tremendous opportunity for congregations, no matter how large or small they are, to respond. How have you seen congregations respond to the needs of and serve the caregivers in the midst of their communities?

Elizabeth Shulman: I’ve seen them do it in very situation specific and unique ways. For example, I had one family where the father had been a bank teller and he was always counting money. As he got further along in his dementia, he was always fingering money or paper. A brilliant congregation member said, “Why don’t we just get some play money? I’ll come and I’ll spend an hour a day.” They would count money. They would come up with costs for items, and he would give her the dollar amount, and she would give him change. It was a really cool way for them to interact. She used her gifts to come up with a great idea and then saw how it worked for this individual.

Now sometimes there’s some trial and error. For those who are willing and interested, God carves a path to have some really tremendous interactions with people despite the dementia.

Jessica Anschutz: Are there ways that congregations have responded on a group level to provide care or is it mostly an individual response?

Elizabeth Shulman: There have been group level responses. As more information and resources are becoming available, I find more opportunities for the person with dementia.

Dementia Friendly Churches is a program that helps design services that are more dementia friendly. Some churches create a room for a caregiver to sit with their loved one. I’ve seen churches include a caregiver and their loved one who is still able to insert bulletins or stuff mailings as volunteers at the church. Caregivers and their loved ones get coffee and sit around a table for an hour or two in the morning to help with office work. The caregiver and the loved one both help out because they’re putting together a bulletin or stuffing a mailing. They both feel worthwhile and useful. Those are some examples that I’ve seen.

Jessica Anschutz: It also benefits the congregation. What a wonderful idea. In thinking about supporting caregivers, talk a little bit about the unique needs of spousal caregivers versus children who are caring for a parent.

Elizabeth Shulman: Spouses share such a physically and emotionally intimate relationship, and then the loved one loses the very person that they would talk to for support. That can be true for children, also, but spouses often lose their main sense of support. To be able to develop friendships or have friendships where you can be open and share about your experience is important. With children, the patriarch of the family may need help bathing or the person you would go to for wise instruction just stares at you blankly. Even within those subgroups, everyone has a story behind their relationship with the person who’s developed dementia. Honoring that relationship and being honest about what specifically is missing or their unique struggles is important. When a caregiver can identify their needs, it’s easier to identify how someone can help.

Jessica Anschutz: As church leaders seek to better support caregivers, what are the things they should keep in mind?

Elizabeth Shulman: They should remember that everyone has their own story. We have a blanket impression of what caregivers may need in terms of general support, but we need not assume that someone should spend more time with a loved one who has been physically abusive. Everyone’s got a story, so it’s important to be open-minded.

The best offer of support is just listening, and then, then, going from there. Remember a lot of times, there are conflicts within families over caregiving. A congregation member may go to their pastor with a list of complaints, and they are probably valid. But the person about whom they are complaining may also have some valid issues. So, to be compassionate and open about all sides of the story is a good starting point.

Jessica Anschutz: That’s very wise advice and insight. One of the things you lift up in the book is the deep sense of loneliness that caregivers report having and experiencing. How can congregations respond and offer support?

Elizabeth Shulman: Congregations can offer support in a number of different ways. One is to speak openly about loneliness from the pulpit. Say, “We have dementia caregivers in our congregation, and I acknowledge their needs or prayer requests.” Set up a box for dementia caregivers to share their prayer requests because, from those prayer requests, you gather needs. Put little blurbs in the newsletters. A person may not be able to attend church, but if they see something acknowledging dementia and the struggles of caregivers, it can help them feel validated. Then congregations can provide resources. There are so many caregiving support groups that are available online. These groups offer a sense of anonymity, so people may feel safer than at in-person gatherings. Facebook, Reddit, and the Alzheimer’s Association all have forms of caregiver online support groups. Share specific information about support groups to help caregivers know where to go. Sharing information helps educate pastors and church leaders.

Jessica Anschutz: Wonderful ideas, and I hope some of our listeners will implement them if they haven’t already done so. As part of the process that you mentioned for local congregations, you said that the aspect for the church volunteers is to look at their spiritual gifts. Why is it important to match the spiritual gifts of the volunteers with the needs of caregivers?

Elizabeth Shulman: It’s important because both parties benefit and find meaning. It’s one thing to provide a duty to someone in need, but I truly believe that God gives us gifts to use them. So, if we can identify something we really enjoy doing — like a hairdresser may really enjoy washing hair. There may be a husband who has never washed his wife’s hair and has no idea how to do it. That woman may say, “I’ll come by once a week, and I’ll do her hair.” She would be using her gift and fulfilling such a desperate need. It would make her feel good, too. The husband would feel good. His wife would probably feel pretty good after having her hair washed. So, think about what someone enjoys doing and how that can be applied to help someone with dementia. I think this is just a great starting point. Wherever there is a need there’s a gift that can go with it.

Jessica Anschutz: And it might be something as simple as washing hair. As you think about the model you developed for Finding Sanctuary, do you see ways that the model could be adapted to address other issues in a community?

Elizabeth Shulman: I do. My model is based on narratives from caregivers. Each group reads stories that caregivers are encountering, coupled with scriptures that can meet those needs. Everybody has a story, whether it’s dementia caregiving or parents of young children. We’ve all got stories and scripture is there to address them. My model identifies the issues but does not stop there. I use the illustration of cooking. The oil on your stove catches fire. So many times, when we encounter a problem or a struggle, we focus on the fire. “Oh, this is going wrong, and this is going wrong.” But we don’t stay there looking at the fire. We turn away from the fire and look for something to put it out. The same is true for any struggle or problem we have. If we continue to regurgitate it and talk about it, the more we encounter those struggles. But if we have faith, turn away, and look at scripture or reframe how we look at a situation, we can find the positive.

I don’t think Jesus was joking when he said don’t worry. I think he was serious. How do we not worry? If we take our attention off the problem, even momentarily, to look for the hope and a solution, I think God will provide. So, my model is to identify the problem, look for hope and for where you can turn, then apply that to the struggle.

Jessica Anschutz: One of the challenges you lift up is that a lot of people have trouble asking for help. How can congregations and church leaders encourage people to ask for help?

Elizabeth Shulman: While it’s hard to ask for help, it’s the caregiver’s responsibility to ask for help. If they’re complaining about not having help but haven’t specifically asked, then it is difficult to respond. Go back to the idea of a prayer box or even say, “It is so hard to ask for help. In your caregiving situation, if it would help for someone to come and sit with your loved one for an hour a week so you can run to the store or take a shower, then let us know, and we’ll find someone.” Name some of those specific common needs. “If you need a meal brought to your house, let us know, and we will come up with a list of people who can do that.”

Jessica Anschutz: What other creative ways have you seen congregations respond to the needs of caregivers and persons with dementia?

Elizabeth Shulman: I’ve seen a group of people build activity boards. You take a giant board, and you bolt different little activities on it — putting a key in a lock, or threading bolts into nuts, things like that — and then take them to someone whose dementia is advanced to the point where they just like to keep busy with their hands. I’ve seen the same for sensory touch blankets where people will make a two-by-two-foot square of different materials — fuzzy, scratchy, etc. — and weave it into a quilt. It gives someone with dementia different tactile stimulations, which can be helpful for keeping them calm and doing something active with their hands.

Jessica Anschutz: That would be a wonderful way to engage congregations that have quilting ministries in providing support for persons with dementia.

Elizabeth Shulman: Another idea is a card ministry. So many loved ones can’t attend church anymore. Sending a card so they know that they’re not forgotten can be huge. It’s not difficult and there are people in churches with that skill.

Jessica Anschutz: I would even go so far as to say there are persons in care facilities that can make phone calls and send cards on behalf of a congregation. What a great way to engage people of all ages in that sort of activity. You could have a Sunday school class make cards that other people could then mail to folks. It could be intergenerational as far as the response goes. As we think about congregations that don’t yet have dementia care ministry, what words of wisdom would you offer to them as they seek to get started and embark upon such a ministry?

Elizabeth Shulman: I think initially just diving in online and looking for resources. There’s this great book called Finding Sanctuary in the Midst of Alzheimer’s. On my website, Elizabethshulman.com, I have devotions. I have a list of hundreds of needs that caregivers have shared.

I also encourage people to go to a dementia care unit. Maybe a Sunday school class could go on a field trip. They could go and visit a member who no longer comes to church and interact with people with dementia, because there’s still this stigma. People don’t know how to respond, so they think, “I can’t really say anything that would be beneficial.” Yet, you could go read a story, look at pictures of old cars, talk about war experiences, or just — baptism by fire — go in and surround yourself with people who have dementia. Check in with yourself and see how that feels. Chances are you would overcome some of your hang-ups with people with dementia if you exposed yourself to it or interacted with them. Doing that I think would be a great step.

Jessica Anschutz: What words of advice do you have for those interactions? How should people respond?

Elizabeth Shulman: If you get a chance to talk to the family members first, ask, “What did your loved one used to do for a living? Do they have grandchildren?” Print pictures of old magazine advertisements or old cars. There are also lists online of questions to ask. People with dementia tend to lose their memory with regard to things that happened recently. Things that happened way long ago are still intact, so go back — “Who was your favorite teacher? Did you have a pet growing up? What was the first car you drove?” Questions like that can help engage.

Jessica Anschutz: Those are great entry points to conversations. As we think about caregivers, I know one thing that I have seen is that they are often exhausted. There is a tremendous need for self-care. From your experience as a caregiver, what advice do you have to offer to other caregivers?

Elizabeth Shulman: Well, take time for yourself. It’s like when you have a little child, you sleep when they sleep. Do something that you enjoy. I think a lot of times, it is difficult to find time. In real time you can practice reframing and looking at a situation differently. An example I use because it’s so prevalent is that caregivers often encounter repetitive questioning. “When’s mom picking me up?” “Well, your mom died 40 years ago.” Dementia care is not about setting people straight or being logical. It’s about offering assurance. So, “When is mom arriving?” “What do you remember about your mom?” “What car is she going to be driving?”

When you’re constantly arguing with a loved one about something that they are truly unable to understand because of the disease process, it makes no sense. It just aggravates you. It makes you more frustrated. Go along with the person — “What time is lunch?” “It’s at noon.” I can remember, with my grandma, we would guess what’s the over/under — “How many times is grandma going to ask, ‘What time is lunch?’” — and make a game out of it for our own sanity. Otherwise, “I just told you. It’s ….” You should answer as though she’s asking it for the first time, because for her it is the first time. If you can reframe and look at something differently, it can take some of the stress and help with some of the exhaustion. Not all, but you’ve got to make tweaks where you can.

Jessica Anschutz: Right. And take the opportunities for a break when you can get them. Elizabeth, the title of your book is Finding Sanctuary. Share with our listeners the importance of finding sanctuary and how you how you interpret finding sanctuary.

Elizabeth Shulman: When I first started writing, I wanted to provide something where people feel safe to share, feel a sense of reprieve and comfort. That’s what I strove to do with this book — to help people identify how to ask for help so that they can have that hour to recharge but also with reframing or appreciative inquiry.

Focusing on the positive is not ignoring the negative. It’s just giving your mind an opportunity to feel good in the midst of chaos, using your God-given imagination to wake up in the morning and imagine how you want the day to look. Studies show that people who focus on positive outcomes are more likely to get that positive outcome. Rather than making the checklist of all the anticipated drudgery things, take a risk and anticipate the positive. What if everything does work out today rather than “What if this happens? What if that happens?” When we look for the hope that God provides, we’re much more likely to find it.

Jessica Anschutz: So true. The importance of positivity can certainly make an impact on caregivers and care receivers. As we think about hope, Elizabeth, what is your hope for congregations when it comes to dementia care ministry?

Elizabeth Shulman: I hope that every church has a copy of my book and any other dementia care resources on their shelves. I hope that churches put as much energy and research into dementia caregivers as they do Vacation Bible School. Every year there are the themes and the banners outside the churches. I would love to see that for dementia caregivers.

Jessica Anschutz: I thank you so much, Elizabeth, for your passion, for your care, for your hope, and for taking the time to share with our listeners about the needs of persons with dementia and their caregivers. Any final words from you for our listeners?

Elizabeth Shulman: No, I just am so appreciative to be able to share my story, and I hope that others find it beneficial. I love dementia. I love talking about it, so thank you so much for having me.

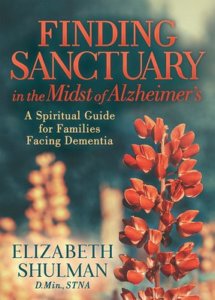

Elizabeth Shulman is author of Finding Sanctuary in the Midst of Alzheimer’s (Morgan James Faith, 2021), available from the publisher and at Amazon.

Related Resources

- Nurturing a Dementia-Friendly Church by Kenneth L. Carder

- As Memory Fades, Ministry Grows: Ministry Alongside Persons with Dementia by Jessica L. Anschutz

- Tapping the Gifts of Homebound Leaders by Susan E. Gillies And Ingrid Dvirnak