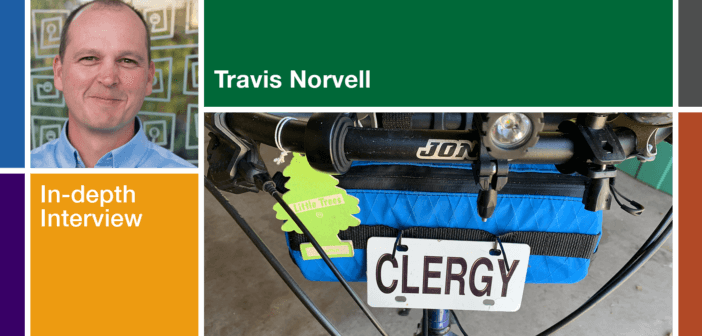

How can your church reorient its posture toward its neighbors and neighborhood? Ann Michel of the Lewis Center Staff interviews Minnesota pastor Travis Norvell on his decision to conduct his ministry by bike, on foot, and on public transportation, and how it revealed new people, new partners, and new possibilities for ministry.

Listen to this interview, watch the interview video on YouTube, or continue reading.

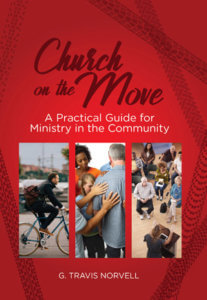

Ann Michel: In the opening of your book, Church on the Move, you share how the decision to give up your car was a turning point in how you experience your neighbors and your neighborhood. Could you share a bit of that story?

Travis Norvell: I had always wanted to try to give up my car, but I didn’t have the courage or sometimes the imagination to do it. Then, I preached a sermon where I asked the question of the congregation, “What are you willing to sacrifice so that others may experience joy?” That night, when I was putting my then 11-year-old daughter to bed, she said, “Hey, Dad? What are you willing to sacrifice so that others may experience joy?” And I just felt ashen. I felt like a complete phony. I felt like I was all talk and no action, and my daughter was calling me out on it. She was very innocently giving me what every preacher hopes for — actually paying attention to the sermon and asking questions about it. I said, “I don’t know. But I’ll tell you what. I’ll know in the morning.”

So, I turned my dining room into a kind of a midlife crisis center. I had my laptop and notebooks and pins everywhere. And I just came up with this idea of selling the car and trying to bike, walk, and take public transit for my job as a pastor. When I told the kids in the morning, they were horrified. I said, “Look, this is my experiment, not yours.” And they took a deep breath and said, “Okay, Dad. We’ll be there for you.” And that’s how it’s got started.

Ann Michel: And how has that changed the trajectory of your ministry?

Travis Norvell: It changed everything. I went to Colgate Rochester Seminary and social gospel is part of my blood. But I realized that I talked a lot about social justice, but I wasn’t really spending much time with the poor at all. But when I started biking and walking and taking public transit, I found myself surrounded with people I had talked about but hadn’t been in community with. And it changed everything about how I looked at transit, at housing, at economics and jobs, bringing all those things into a new light.

And it also changed the trajectory of the church. The church had always thought of itself as a destination church. But biking and walking and taking public transit showed me that we were really a much closer church. About 75 percent of our people were within three to five miles of the church and only 25 percent were driving in from other places. It reoriented us toward our own neighborhood. But the biggest realization was that we had no idea who our neighbors were any more.

Ann Michel: Let’s talk parking lots. It’s long been assumed that a church can’t grow without ample, convenient parking. You have a really different way of thinking about parking lots. What are some of the blessings and curses of a church parking lot?

Travis Norvell: A parking allows you to become a “de-neighborhood church.” It allows people to drive in from miles around, come to church and worship, and then get in their cars and go home. Now that can be a blessing to those coming from a distance to seek the spiritual nurture and support of the congregation. We should never hold that against someone. But for most city neighborhood churches in America, if you have a parking lot, it means someone’s house was taken so that you could park your car there. And you need to respect that and use it as much as you can to honor that it was formerly someone’s dwelling place.

I think we need to reimagine what we can do with a parking lot. In most instances, a church is only using its parking lot for at most six hours a week for the temporary storage of an automobile. The rest of the week, it remains empty. So, what are the things that you can do with a parking lot? Here in Minnesota, there’s a guy that started straw bale gardening. You can take just straw bales and put them in a parking lot, and two parking spots can produce enough vegetables and produce to feed a family of four for a year.

You can think about basketball. There’s a Methodist church in my hometown that put up nine-foot basketball posts. And it was the greatest event in the world for us because all of us could finally dunk the basketball. There were 150 kids on Saturday and Sunday mornings waiting to play. But the church saw us as a nuisance. So, one day they came out with a blowtorch and a grinder and cut the polls down. And I thought, “You had a makeshift youth group that people would die for right there in your parking lot.”

During COVID we found that we could use our parking lot for worship. We could do movie nights. We could have bands come out and play. There’re just countless things you can do. Labyrinths. Blood mobiles. Bike courses. If you look at the Dutch in the 1940s when they really started thinking about biking, church basements were bike schools. There are so many other things we can do other than just a park a car. And I like to think of it more as a church plaza than a church parking lot.

Ann Michel: Biking and parking are really just part of a larger vision you have for how churches can relate differently to their surroundings. You write about a church building as an asset for making a church more present to the community. Could you describe some of the ways your church has done this?

Travis Norvell: We to try to ask, “Does the outside of our building communicate our inside values and what do we do on the inside?” We looked at our floor space and how often it was being used. Even though we have a preschool, meals on wheels, on-site counselors, and community groups that use our space, there are still lots of times when it’s not being used. We have a beautiful baby grand Steinway piano that remains unused most of the week. But now we have a jazz musician who comes in and practices throughout the week. And we get a twofer. He gets to practice. We get to hear great music during the week. And then on most Sundays, if I need him to play, I’ll say, “Hey, can you come and play?” At Christmas, when I want to do a Christmas pageant, I asked, “Can you play the Peanuts Christmas song?” And he came and played the Peanuts Christmas song.

There’s a Somali artist here in town that was looking for a space to build a healing hut and couldn’t find one. So, we said, “Well, you can build it in our sanctuary.” So, right now, in the back of our sanctuary she’s building this hut. And we’re going to have open times for people from the community to come by and see how she’s working. And on Fridays, she is going to provide Somali tea and treats for people that want to stop by and check it out.

Just like with parking lots, there are just so many other parts of the church building we could be using more. I think the church library is a great place to start. Let people come in and use it. Where else can you find a rich variety of theological books right on the shelf and not even have to request or wait in line for them? Think about the church kitchen. We have a history of great kitchens and meals. But, you know, six days out of the week it’s never used. Why aren’t there hundreds of little entrepreneurial businesses in church kitchens? So just trying to think of all the aspects of our building that can be used for the benefit of the community.

Ann Michel: You describe your ministry context in Minneapolis as a “city neighborhood.” It’s a relatively dense urban setting with a lot of foot traffic. I’m wondering how some of your ideas might apply to churches in deep exurbia or rural areas?

Travis Norvell: In suburban, exurban, and even rural areas, people still need places to come and congregate. Places to hear music. Places to meet. And churches can provide that easily. I took a sabbatical a few years ago, and my wife and kids and I did a lot of walking in rural Scotland. And churches were wonderful little places of hospitality along the pilgrimage trail. The doors were open. Some had a little tea kitchen set up. And anybody could just walk in, get a cup of tea, and sign the guest book. I think that churches can again be way stations like that, wherever we are, providing space and places for some quiet meditation.

I don’t think we see our buildings as the wonderful jewels that they are. With modern architecture, it’s really hard to find a place with the grandeur and physical space that our congregations and churches provide. Just a place to sit down, relax, catch your breath, and think about life for maybe five minutes. There doesn’t have to be a church service. There doesn’t have to be anybody there. I think these kinds of spaces are still very needed in rural settings, in the exurbs, in the suburbs.

Ann Michel: You present your vision of connecting with the community through the lenses of evangelism and community relations. But your ideas also have profound implications for our stewardship — for environmental stewardship, stewarding the church’s physical assets, for staffing, and so forth.

Travis Norvell: This venture changed the way I look at stewardship. Before, there was always scarcity. There was never enough money. There was never enough time. There were never enough people. But, when you ride your bike or walk or take public transit, you’re really not moving very fast, and it gives you time to think about things. How can we apply a slow church approach to stewardship? We found that if we use our building in a variety of ways there’s more than enough money around. People are looking for low cost or below market rental space. And when you’re out in the community, you start meeting people, and you start realizing that there are people that are willing to partner with you. There is no scarcity of people. People are everywhere. It’s a matter of finding ways to partner for the sake of mission. With regard to money, if you’re so scarcity bound, your vision becomes limited, and you’re not seeing the real possibilities around you. But when you ride a bike, when you’re walking in your neighborhood, when you’re talking to people, you know there is abundance all around.

We really found that out after the George Floyd murder. We’re about a mile and a half from George Floyd Square. And because we’d been working in the community, we had a lot of connections. And when we put a call for donations on our webpage and social media, within three weeks we had over $50,000 from people in eight states and two countries. But we knew where to put those funds. We knew the right people to talk to. We knew the areas with the most need. And we could report on those needs really quickly, with pictures and stories and narratives. There wasn’t a scarcity of money. There was abundance. But you have to tell the right story, be in community with the right people, and make yourself vulnerable and open.

Ann Michel: How do you see your ministry and urban ministry in general changing, given the challenges of COVID and some of the other major occurrences in the last two years?

Travis Norvell: Well, I think everything has changed. Nothing feels the same. Talking to colleagues from around the nation, it seems there are people who are saying, “I’m just not coming back.” Probably 20 to 30 percent of people. I think COVID may have just been the nudge that caused them to leave the church. But then, there’s another 20 to 30 percent of people that are interested now that weren’t interested before. So, that’s a whole new nudge in a positive direction.

We’re rethinking everything now. The language we use. The partnerships we’re in. How we’re using our money and resources. How we plan. I mean, what is long term right now? Two years? What’s working right now may not work in six months. So, for us, it’s been about being nimble. How can we be open to the movements of the Spirit? How can we really make ourselves vulnerable again? This may be the time, to use a metaphor Pope Francis gave us, for the church to be a field hospital, not a mighty fortress. I feel that’s kind of where we need to be.

Ann Michel: In the opening of your book, you wrote, “We’ve heard it said small churches will be extinct by 2050. But I say small churches are exactly what the world needs at this time.” Why do you think that’s so?

Travis Norvell: I think people need to be known. They need their names and their stories known. They need a place where they can really delve into life’s questions and meanings, a place to ask some dangerous questions, to be messy, to be themselves. I think small churches provide the most beautiful example of that. We’re at a place in our country right now where, if you disagree with someone, you either unfriend them or you just say goodbye. But I think small churches give us the capacity to get beyond just getting along and appreciate someone for who they really are. They may not be where you are. You may not be where they are. But over time, relationships change, and hearts get broken. And a broken heart is an open heart.

People are just available in different ways in small churches than in large churches. I love large churches. I grew up in one and it nurtured me. But I really feel that in a small church atmosphere I’m more myself and other people are allowed to be more themselves.

Ann Michel: I want to end on a fun note. Church on the Move is the first church leadership book I’ve read that includes a recipe collection. Why did you include recipes like “100 Mile Granola,” “Church Plaza Pizza,” and “Instapot Pulled Pork” as part of your book?

Travis Norvell: So much of church is based around food. So much of Jesus’s ministry revolves around food. And think about all the church cookbooks, too. It seems so central to our faith, so to me the question is, “Why don’t all church leadership and theology books have recipes?”

Related Resources

Related Resources

- Church on the Move: A Practical Guide for Ministry in the Community (Judson Press, 2022). The book is also available at Cokesbury and Amazon.

- Making Your Ministry Present in Its Physical Space by Travis Norvell

- How One-to-One Conversations Reintroduced a Church to its Neighbors by Travis Norvell

- “It’s Time to Reimagine the Church Parking Lot,” by Travis Norvell, Christian Century, March 10, 2022.

- Reimagining Church Buildings by Dave Harder

- Taking Church to the Community Video Tool Kit