How would you preach next Sunday if a mass shooting, a natural disaster, or a public health crisis shook your community? Sadly, such events are so common that every preacher needs to be prepared. Preaching professor Kimberly Wagner outlines five characteristics of preaching in the wake of mass trauma that create a safe space for people to lay their experiences and brokenness down before God and one another.

A preacher speaking in the aftermath of mass trauma is more than simply a reporter or community counselor. Preachers are summoned to contend with the experience of trauma as well as the truth of the gospel. Each preacher stands with one foot in the fractured stories of the community and one foot in the stories and promises of the faith. Unlike journalists or elected officials, preachers are entrusted to locate this experience of trauma theologically, even as they take seriously its impact on individuals and communities.

In the aftermath of a mass traumatic event, communities exist in a liminal space, an in-between space: between the atrocity and rebuilding, between disbelief and reimagining, between the evil that has happened and the recovery to come. Such an in-between space calls for an in-between word — a word located in the eschatological tension between what has been broken or lost, on one hand, and the anticipation of God’s promised hope on the other. Such preaching does not shy away from hard emotions, grief, or lament, but embraces and even models these hard truths in the preaching event. At the same time, this preaching does not resist the longing for hope or the promises of God that, though not always sensed in the moment, are already present and coming toward us. Such preaching lives in the tension between brokenness and hope, between death and resurrection, between loss and redemption.

On the one side of this in-between word sits the reality of brokenness, death, and loss. Preaching in this eschatological tension requires sermons to name, acknowledge, and make room for people’s fragmented, fractured, and broken realities. This side of the tension invites preaching that embodies five essential characteristics.

1. Bold truth-telling

Preachers need to be honest about what has happened and what has been lost or broken. This means not simply being attentive to the facts and figures or the timeline of what has occurred but also naming other losses, such as damage to a sense of safety or security, confidence in the future, or a feeling of peace and control. Preachers are invited to dig deeper than what is reported on the news and name the ways such events might shake the foundational beliefs and convictions of the community.

2. Acknowledging complex emotions

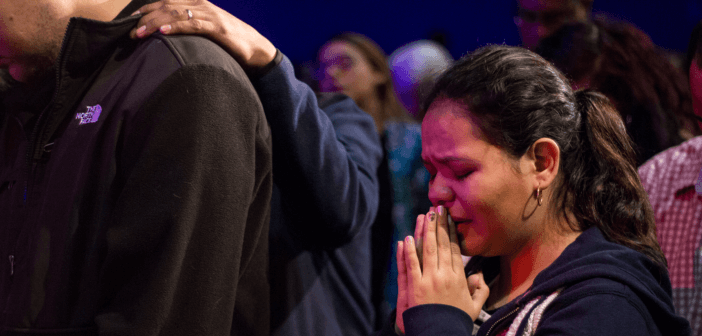

People respond differently even to the same event. Some may feel deep grief; others may be in disbelief or shock; others may turn to anger; still others might feel relief or even gratitude; some may wrestle with survivor’s guilt; other may feel compelled to escape or push aside the pain; and many people may feel any combination of these in waves or all at once.

One of the first things to go in the face of trauma is the language needed to clearly articulate one’s story and situation, even to express a sense of self amid it all. Preachers offer the gift of language when they simply, clearly, and honestly say, “This is what we are experiencing. This is what we may be thinking and feeling.” Naming grief, guilt, and gratitude (among other feelings) invites people to bring what they are carrying into the preaching space before God and one another. By allowing for mutual understanding and empathy, the preacher may help the community work to resist some of the ways mass trauma threatens to pull communities apart.

3. Naming lingering and even unanswerable questions

This is not permission to completely dodge the challenging realities or eventual wrestling with theodicy (how a good God can cause or let bad things happen) that are bound to unfold. However, it is an invitation for preachers to acknowledge and model faithful questioning without rushing to quickly to solutions. When preachers feel compelled to answer challenging questions too quickly, they may find themselves leaning on cursory platitudes or token theological adages. Preachers would be wise to be slow in suggesting answers both to avoid giving superficial responses as well as to avoid offering responses that might feel superficial if they cannot yet be received. Modeling faithful wrestling permits the community to bring their questions and disorientation before God and one another.

4. Naming communal impacts

Preaching is a communal event, so preaching is an appropriate time and place to note the impact of the event not only on individuals, but also on the whole community. It is important for preachers and community leaders to articulate the nature of community trauma, acknowledging ways the whole community has been changed. After traumatic events, there is often a longing to “get back to normal” or a sense that if we can just push through, we can go back to how it was before the event. However, trauma lingers. Trauma changes people and communities. There is no return to good as new and no going back to a familiar normal. Some communities may recover and cultivate resiliency, but no person or community can ever return to the everyday existence or innocence of life before the mass traumatic event. To acknowledge that the community will be forever changed by this event invites honest reflection about what has been lost. Such honesty opens the way for the community to prepare the ground for communal reconstruction and reimagination, not merely a return to some impossible-to-recover past.

5. Clarity about the existence and nature of sin and evil

In mass traumatic events, communities may find themselves confronted by violence, evil, hate, destruction, loss, and hurt at a level never previously experienced. Preachers are called to be forthright about destructive forces in the world — even the ways we participate in, compound, or benefit from such realities. At the same time, preachers should also be careful to avoid labeling others as evil. Especially in instances of mass violence or disasters caused or exacerbated by human error or incompetence, there is a natural tendency to demonize or vilify perpetrators or those in leadership. Although accountability is important and is foundational in seeking justice, preachers ought to resist the inclination to dehumanize others and risk perpetuating or accentuating the hate, hurt, or violence.

Ultimately, to name, acknowledge, and open opportunities to recognize hurt, pain, loss, and brokenness allows the congregation to bring its own fragments of experience into the worship space and the preaching event. By doing this in the preaching moment, there is an implicit blessing of life’s fragments, and people are offered assurance that their experience is not beyond the love and grace of God or the care of the community. Through attending to the experience of fracture and brokenness, the preacher creates a safe space for people to bring whatever scraps of experience they carry and lay them down before God and one another.

Excerpted from Fractured Ground: Preaching in the Wake of Mass Trauma. © 2023 Kimberly R. Wagner. Used by permission. The book is available at Westminster John Knox Press, Cokesbury, and Amazon.

Excerpted from Fractured Ground: Preaching in the Wake of Mass Trauma. © 2023 Kimberly R. Wagner. Used by permission. The book is available at Westminster John Knox Press, Cokesbury, and Amazon.

Related Resources

- Preaching in the Wake of Mass Trauma featuring Kimberly Wagner — Leading Ideas Talks podcast episode | Podcast video | In-depth interview

- Does Your Church Need a Disaster Ministry Plan? by Jamie D. Aten and David M. Boan

- 10 Things Great Preachers Do Differently by Charley Reeb